Nobel laureate economist Robert Merton says David Murray’s Financial System Inquiry must fundamentally shift how Australia thinks about superannuation. He says the desire to maximise lump-sum balances at retirement is excessively risky; the focus should be on ensuring retirement income is enough to meet a desired standing of living.

Source: AFR – 6 Nov 2014 (Paywalled)

I completely agree with this paragraph…in fact, I would say its worse than that as my recent personal experience working with advisers suggests there is still a strong culture of short termism with the focus on maximising returns today as opposed to between now and retirement. However, despite my agreement with the problem, the solution is definitely not a product or super fund, as alluded to by Merton…

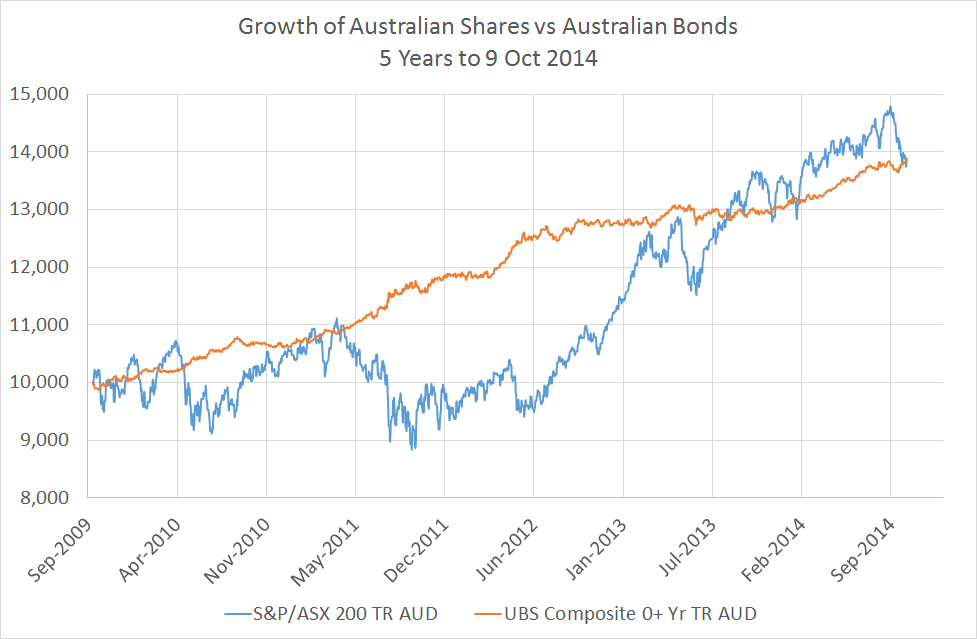

…too many super funds are failing to de-risk balances as employees approach retirement, exposing them to market volatility which could slash their retirement incomes.

…But given this Nobel Prize winning Economist is currently consulting to a product provider then this view is not surprising.

The only solution to this retirement income problem comes from high quality, ongoing, personalised, financial planning. A product can never be personalised and efficiently consider their investor’s needs because they are all different. Investors have different net assets, different savings abilities, different lifestyle costs, and different risk tolerances, so any product solution looking to optimise these issues across a cohort of thousands is kidding themselves…but there is still opportunity for improvement so good luck to Merton and his clients.

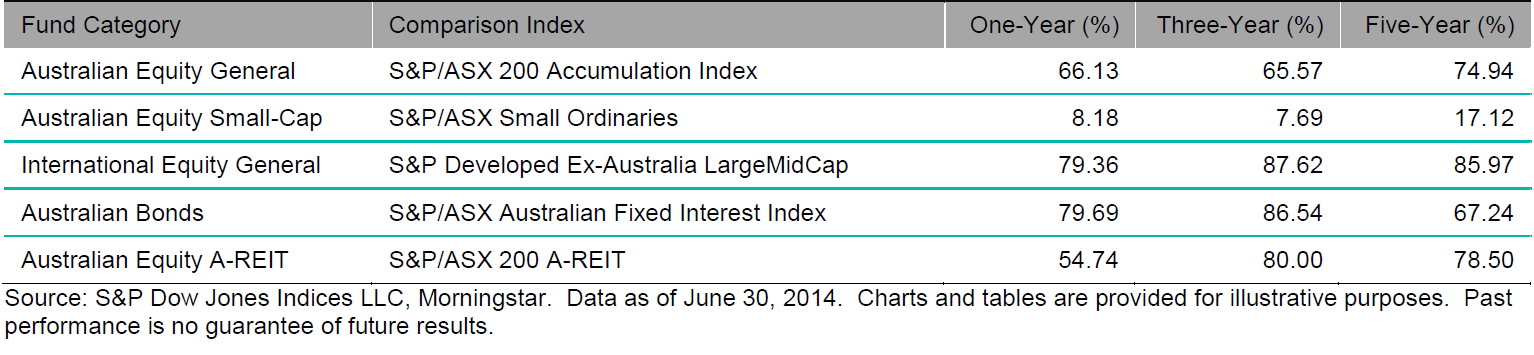

So if providing high quality personalised financial planning can make a difference, why aren’t they doing so? I think the opening paragraph still gives the primary clue in that the financial planning focus in accumulation is not focused on providing an adequate retirement income to meet a desired standard of living.

A desired standard of living can be calculated from a budget….its not hard but its rarely done. Taking the time to estimate a household budget can identify savings opportunities, insurance needs, and those non-discretionary expenses that are likely to endure into retirement…its a very powerful exercise which is too often left out of the financial planning process because its importance is underestimated. A superannuation fund is unlikely to ever collect this detailed information…if it did, the financial planning industry would be in deeper trouble than it is now as not enough financial planners collect it now.

So the budget will provide an indicative retirement income, throw in a few estimates of other likely costs in retirement and you have a reasonable estimate of the desired retirement income…providing for this should be the primary goal. This income estimate leads to the magical figure to provide financial security…or for some, financial independence.

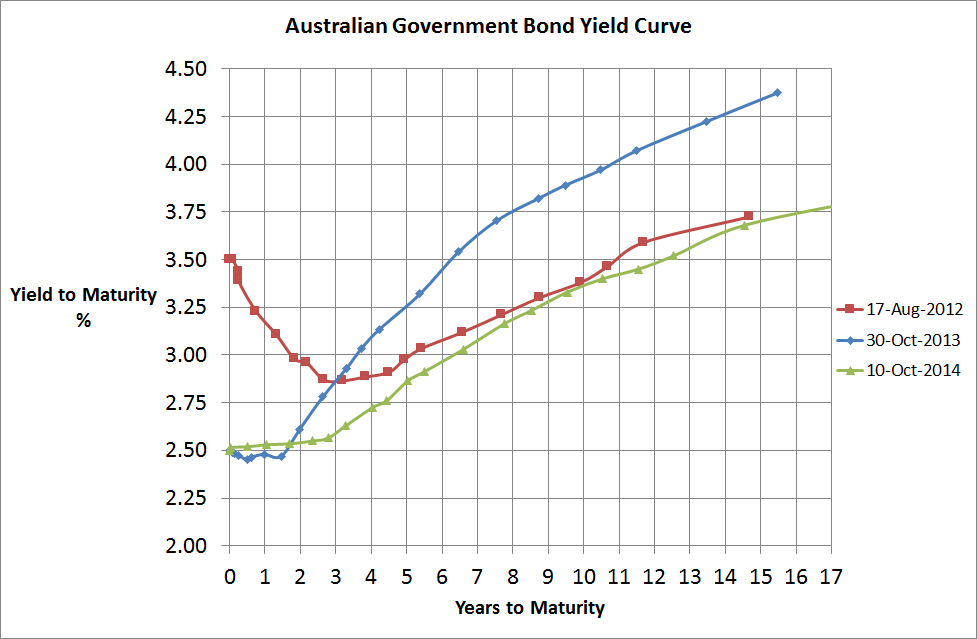

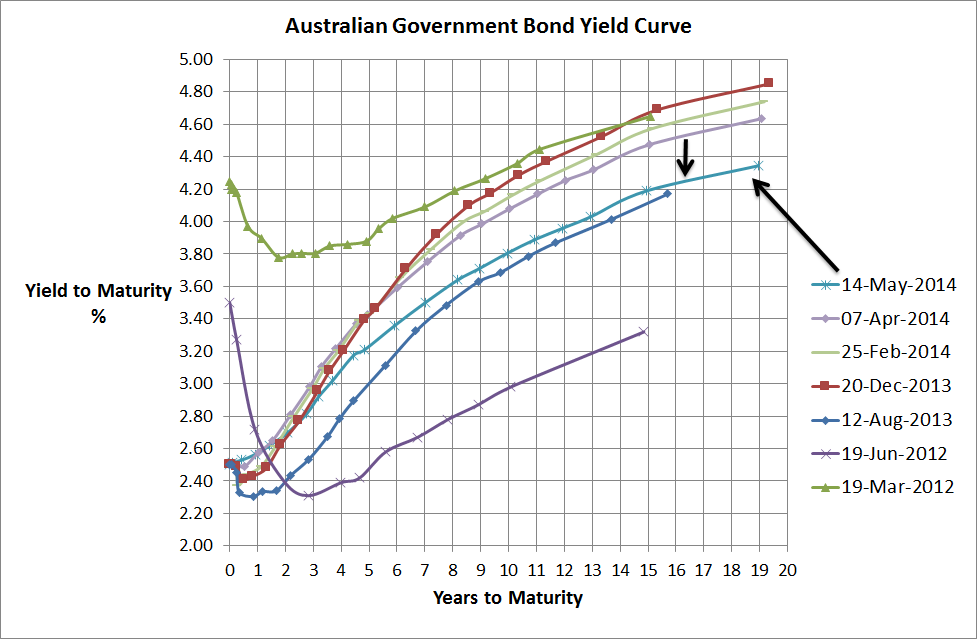

To calculate what we need to provide this retirement income we simply look up lifetime inflation linked annuity rates. Currently a couple of around age 65 will get inflation linked income at around 4%…so to provide an inflation linked income of ~$60,000pa requires around $1.5million in today’s dollars. This is an example of the capital goal at retirement BUT it is in today’s dollars, so moving forward it must be adjusted for inflation, plus, it is using today’s interest rates, so will also adjust as interest rates go up and down…which therefore results in moving annuity rates. Finally, the desired lifestyle spend may change so this needs to stay updated also as part of the financial planning process.

Now, I know many investors and financial advisers will object to my use of inflation linked lifetime annuities from a life company because there is a belief that they offer returns that are poor and they can do better. I’ll be succinct…noone can do better without taking on some risk…therefore there is a risk of failure if you choose to ignore the inflation linked lifetime annuity rates so you probably need to increase the capital goal in today’s dollars above that of the annuitised value…just in case….happy to argue this point another time. Please note, I’m not saying inflation linked lifetime annuity rates are good…they’re just one of the closest investments we have representing the risk free inflation-linked rate for retirement…so by definition as a risk free rate approximation of course the returns should be low.

Finally, using a client’s net assets, and a conservative estimate for future net savings, the financial planner can calculate the desired real return for achieving the desired capital goal…this desired real return should then dictate the strategy or asset allocation of the investment portfolio and must adjust regularly based on changing goals, savings, and investment performance…much easier said than done…but definitely doable. The final point to the recommended strategy is that the desired real return must consider risk tolerance levels…and if the return goal is too high for tolerance levels…then so too may be the retirement income goals, so adjustments are a must.

What this all adds up to is a process that is personalised, objectives based, and adjusts according to client needs, circumstances, goals, market conditions, and clearly requires an ongoing advice relationship. In comparison, a product solution will always be sub-optimal and always reliant upon strong markets. This path dependency (i.e. market performance reliance) is why life-cycle solutions will never replace good financial planning and whilst they may be good solutions at a cohort level, will always be a poor solution for an individual.